Catching Them All: Zero and Few-Shot Pokémon Detection with VLMs

Building an AI system for image or video understanding typically requires large labeled datasets and extensive training. However, in many real-world scenarios:

- Labeled data is unavailable or expensive.

- Training or fine-tuning is resource-intensive.

- The task involves many categories and must generalize easily.

This project explores how to build a practical visual recognition pipeline using vision-language models (VLMs) and zero- or few-shot learning — without manual labeling or retraining.

Pokémon detection is used as the case study: a multi-class visual task with limited supervision, showcasing scalable and flexible recognition using modern multimodal AI models.

📘 You can explore the full pipeline here: Full Notebook: Pokémon Detection with VLMs

This post is part of the Generative AI Lab, a public repository that explores creative and practical uses of LLMs, Vision-Language Models (VLMs), and multimodal AI pipelines. If you are curious about how these systems can be chained together to automate creative workflows, feel free to explore the other blogs in the repository to discover more exciting applications.

📚 Table of Contents

- 🧠 Zero-Shot Classification with CLIP

- 🧪 Few-Shot Classification with CLIP Prototypes

- 🔁 Dataset Expansion via Web Search

- 🕵️ Zero-Shot Object Detection with Grounding DINO

- 🧭 Zero-Shot Object Detection with OWLv2

- ✅ Conclusions

🧠 Zero-Shot Classification with CLIP

The first step uses OpenAI’s CLIP model (openai/clip-vit-base-patch32) to classify video frames without any training. CLIP belongs to the family of vision-language models that jointly process images and natural language to enable cross-modal understanding.

It uses a dual-encoder architecture — one for images and one for text — trained to align paired image-caption data in a shared embedding space.

For each frame, the model computes an image embedding and compares it to embeddings of class names like "Pikachu" or "Charmander". The class with the highest cosine similarity score is selected as the prediction.

- No training or fine-tuning is required.

- Multiple class prompts can be evaluated in a single pass.

- Class similarity scores provide confidence indicators.

This approach demonstrates how a pretrained vision-language model can perform visual classification in a flexible, open-ended setting using only descriptive text prompts.

A short Pokémon intro video (~1 minute) was sourced from Archive.org and used as the test video throughout this project.

🔗 https://ia902305.us.archive.org/35/items/twitter-1421216532307267595/1421216532307267595.mp4

📊 Observations from Zero-Shot Classification

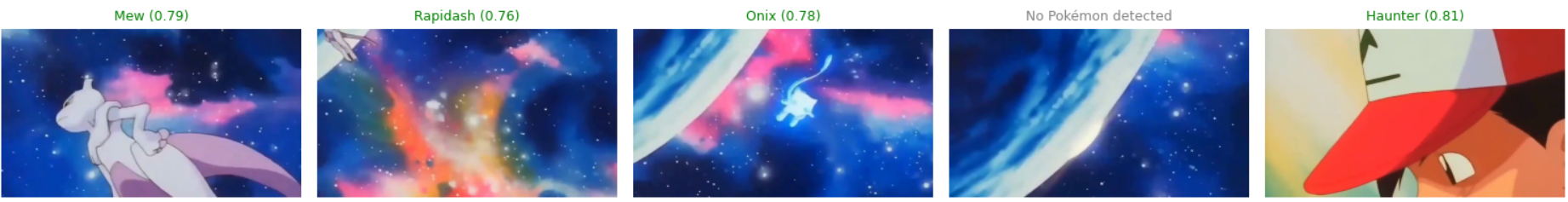

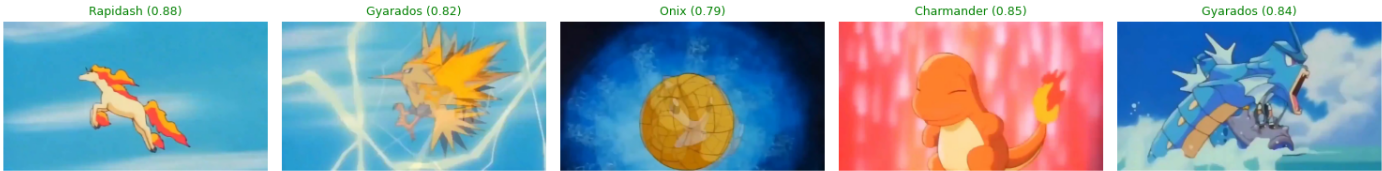

The example below shows CLIP’s predictions across selected frames from the test video.

- In the top two rows, the model correctly identifies the visible Pokémon using zero-shot classification.

- The model is limited to a single prediction per frame, even when multiple Pokémon are clearly present.

- In the final row, where no prompted Pokémon appear, CLIP produces incorrect guesses—often influenced by dominant colors (e.g., blue areas predicted as Squirtle, red/orange as Charmander).

🧪 Few-Shot Classification with CLIP Prototypes

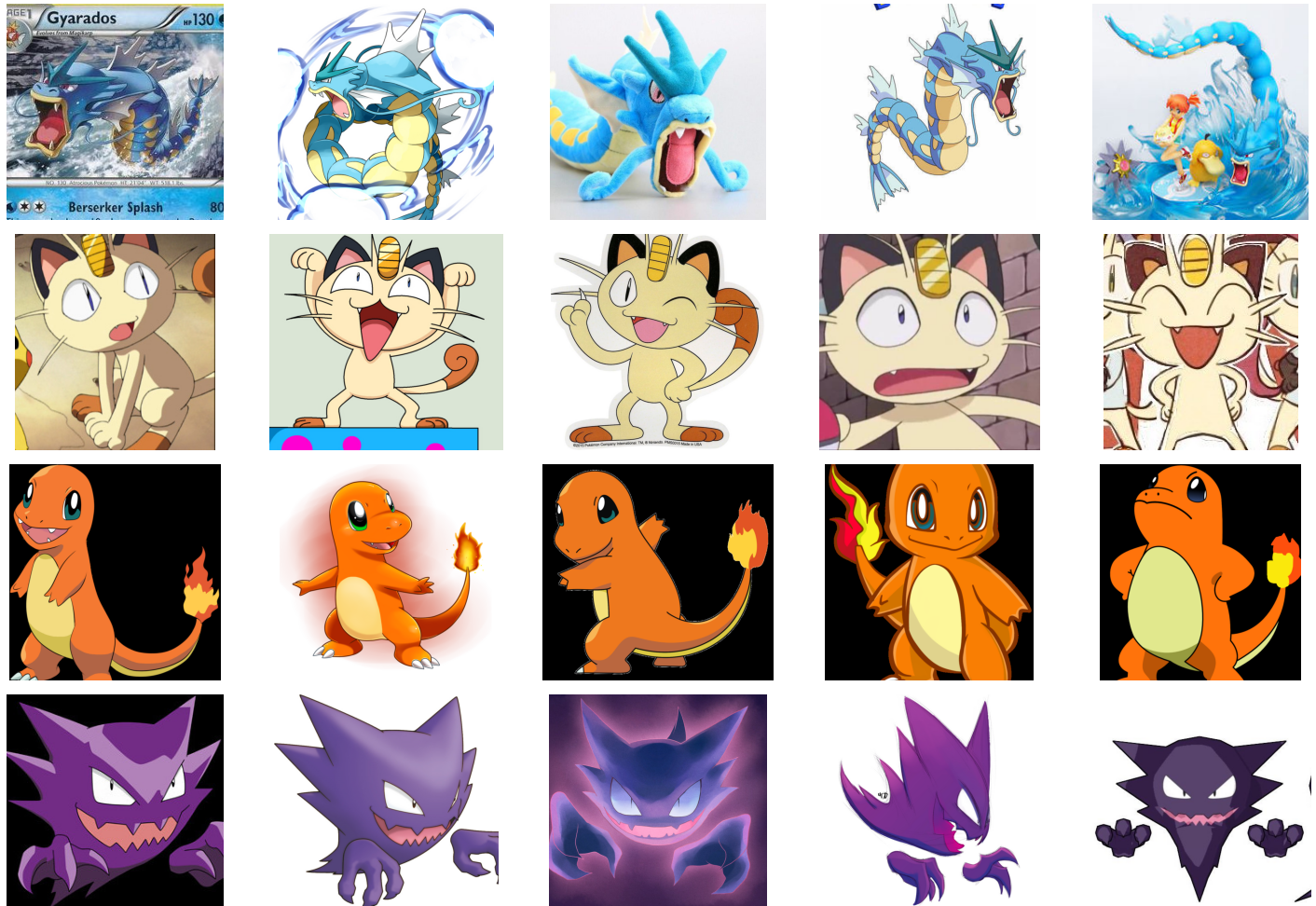

To go beyond zero-shot limitations, we adopt a few-shot classification strategy using a labeled Pokémon dataset from Kaggle, containing ~50 images per class.

- 📁 The dataset was uploaded to Google Drive for easy access within the notebook.

- 🎯 A subset of Pokémon classes was selected—focused on characters visible in the test video.

- 🧠 For each class, CLIP embeddings are computed and averaged to create a class-level prototype.

- 🆚 During inference, new video frames are classified by comparing their embeddings to these prototypes using cosine similarity.

This method improves prediction accuracy while requiring only a handful of labeled examples per class.

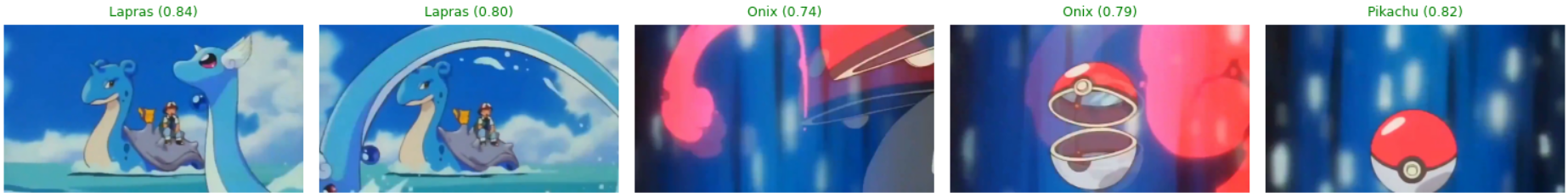

📊 Observations from Few-Shot Classification

- The model successfully classifies a wide variety of Pokémon with high confidence (e.g., Mew, Pikachu, Squirtle, Pidgeotto).

- It struggles when no Pokémon is present in the frame—false positives occur due to background or scene context.

- Non-Pokémon elements like people or Pokéballs sometimes trigger incorrect predictions.

- The confidence threshold can be adjusted to filter out low-certainty predictions and reduce noise in such edge cases.

🔁 Dataset Expansion via Web Search

While the few-shot classifier performs well on Pokémon seen during prototype construction, it struggles with unseen objects such as Ash or a Pokéball, which are not part of the initial support set.

To address this limitation:

- 🌐 Publicly available images can be retrieved for new categories.

- 📸 This method allows for low-effort dataset expansion without manual labeling.

- ⚠️ The quality and relevance of the results depend heavily on curation.

This approach highlights a practical way to improve recognition performance in zero- or few-shot settings by closing key data gaps.

⚠️ Considerations for Dataset Expansion

- Retrieved images often include unrelated elements (e.g., Ash alongside other characters), which may confuse the model.

- Matching the visual style, resolution, and framing of the test data is important to reduce domain shift and ensure consistency.

🕵️ Zero-Shot Object Detection with Grounding DINO

This step introduces Grounding DINO (IDEA-Research/grounding-dino-base), a vision-language model designed for zero-shot object detection using natural language prompts. Unlike classification, which assigns a single label to an image or frame, object detection also identifies where the objects are by drawing bounding boxes around them.

Grounding DINO belongs to a newer class of multimodal models that tightly integrate vision and language. It uses a transformer-based architecture to predict object regions conditioned on free-form text input.

- 📝 Prompts like

"a Pokémon"or specific names guide the model. - 🎯 The model outputs bounding boxes for objects that match the prompt.

- 🔍 Detection is flexible and open-ended — no fixed class vocabulary or retraining is required.

This makes Grounding DINO well-suited for detecting multiple objects in dynamic scenes, directly from descriptive text. It enables general-purpose object localization without supervision, bridging visual and linguistic domains effectively.

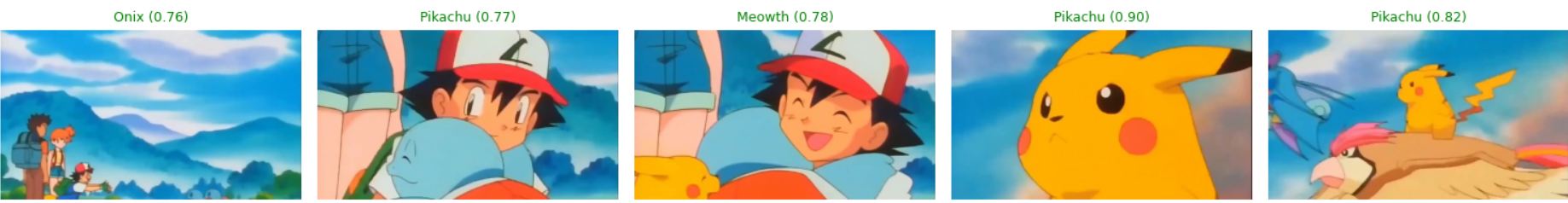

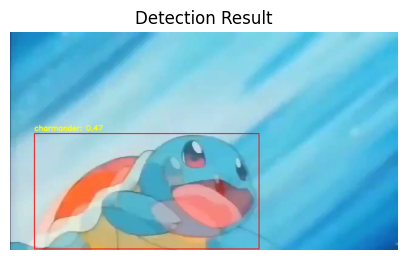

📊 Observations from Zero-Shot Object Detection with Grounding DINO

✏️ Prompt Sensitivity in Grounding DINO

The choice of prompt can significantly influence detection performance:

- 🧠 A general prompt like

"pokemon"results in higher confidence and tighter bounding boxes. - 🧾 Listing specific classes (e.g.,

"squirtle, charmander, bulbasaur") may yield correct detections, but with lower confidence or less optimal localization. - 🎯 This highlights Grounding DINO’s sensitivity to prompt wording—phrasing matters in zero-shot detection tasks.

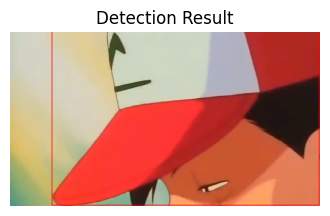

👥 Adding ‘Person’ to the Prompt

- When no Pokémon are present but a person is visible, adding

"person"to the prompt helps guide the model. - 🧭 This improves relevance by reducing false positives and enabling more accurate detections.

- 📌 In this example, the original prompt predicts a Pokémon; the updated prompt correctly identifies a person instead.

- The model correctly detects a variety of Pokémon (e.g., Squirtle, Rapidash, Lapras) and occasionally persons (e.g., Ash, Team Rocket) when the “person” class is included in the prompt.

- It handles multi-object scenes reasonably well, identifying multiple characters in the same frame in some cases.

- However, it still struggles in crowded scenes—often missing one or more objects when both Pokémon and people appear together.

- The model also confuses Pokéballs with Pokémon, even when “pokeball” is explicitly included in the prompt.

- Some bounding boxes are imprecise or attached to the wrong object, especially when characters are occluded or small.

🧭 Zero-Shot Object Detection with OWLv2

This step introduces OWLv2 (google/owlv2-large-patch14-ensemble), a vision-language model designed for open-vocabulary object detection using natural language prompts. OWLv2 improves upon earlier models like Grounding DINO by offering stronger generalization and more robust object localization.

OWLv2 belongs to the family of transformer-based vision-language models trained on image-text pairs with a focus on detection tasks. It leverages a unified architecture to understand both images and free-form textual queries and localize relevant objects in a zero-shot setting.

- 🔍 Uses a powerful visual backbone and multi-scale features for higher precision.

- 🌐 Trained on a broad set of vision-language data for better open-domain generalization.

- ✏️ Less sensitive to the exact wording of prompts compared to Grounding DINO.

- 🎯 Supports detection of multiple, diverse objects in complex scenes without fine-tuning.

OWLv2 demonstrates how modern detection models can be guided entirely by text to identify and locate objects with high accuracy — even in cluttered or unseen scenarios.

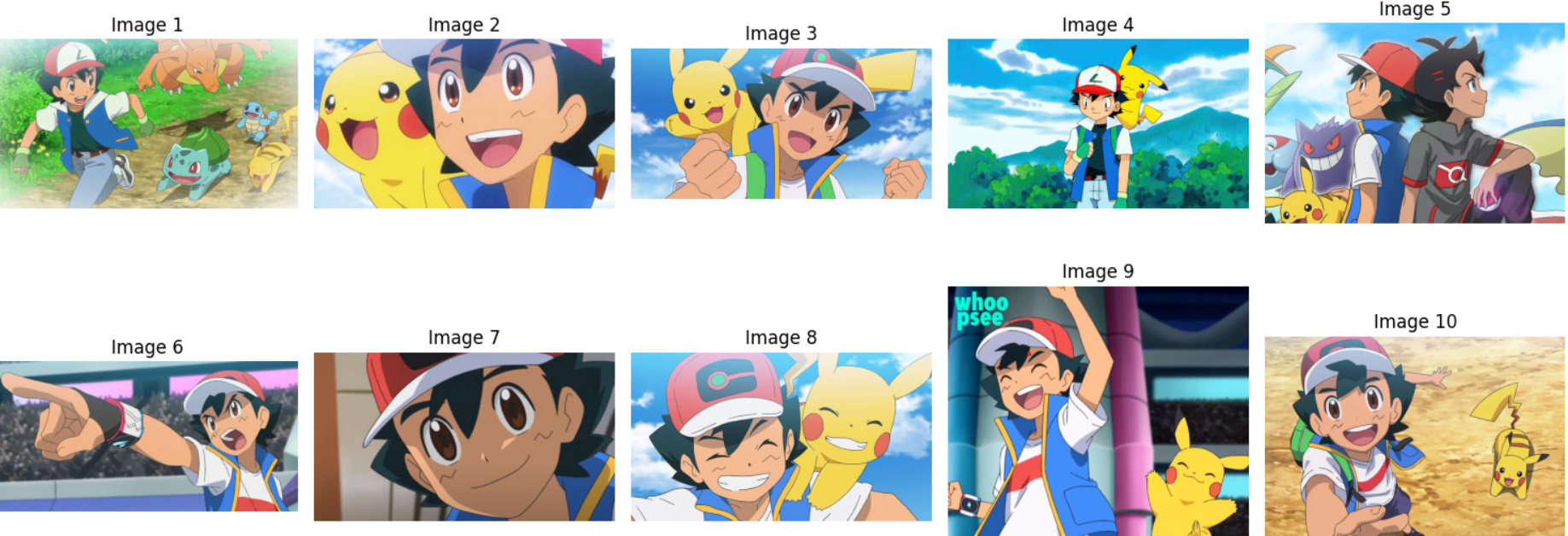

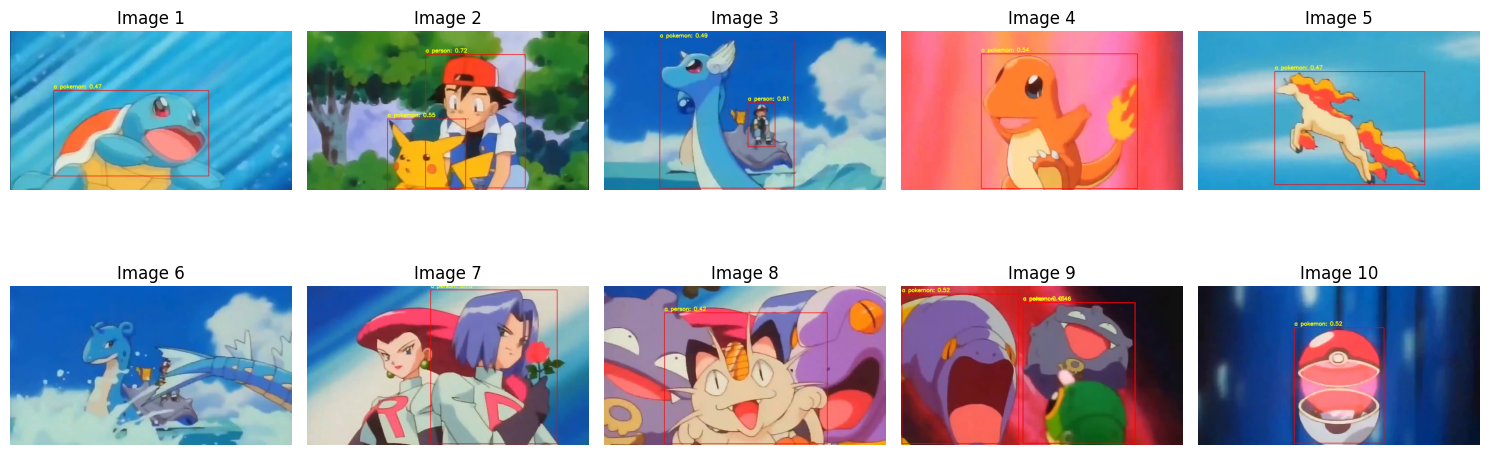

📊 Observations from Zero-Shot Object Detection with OWLv2

The OWLv2 model delivers robust results across diverse Pokémon frames using the prompt:

["a pokemon", "a person", "a pokeball"]

- ✅ Stronger performance than Grounding DINO, with more accurate box placements and reduced false positives.

- 🧠 Successfully detects objects like Pokéballs, which were previously missed or misclassified.

- 🔍 Overlapping boxes or redundant detections could be filtered using Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) for cleaner results.

- ⚙️ Further refinement is possible by tuning the minimum score threshold to filter out lower-confidence predictions.

- 💡 Overall, OWLv2 offers a powerful zero-shot detection solution—no custom training, yet it generalizes impressively across the Pokémon universe.

✅ Conclusions

This project demonstrated how to build a zero- and few-shot Pokémon recognition system using modern vision-language models — all without any model fine-tuning.

- CLIP was used for image-level classification, both in zero-shot and few-shot configurations.

- Grounding DINO enabled flexible, prompt-based object detection without predefined labels.

- OWLv2 improved detection accuracy and robustness across complex scenes and diverse objects.

Each model served a specific role in the pipeline — showcasing how different AI components can be chained together to solve real-world problems under data-scarce conditions.

For further improvement:

- Detected bounding boxes from OWLv2 could be passed to the few-shot CLIP classifier to assign more accurate Pokémon labels per object.

- Alternatively, a multimodal large language model (MLLM) like Qwen-VL or Mistral could process the cropped detections and reason about the characters visually and linguistically.

- Applying post-filtering, box refinement, or even temporal smoothing could further stabilize the results across video frames.

No single model does it all. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each tool — and how they can complement each other — is key to designing AI systems that are practical, flexible, and effective. Multimodal AI is not just about having powerful models, but about making them work together seamlessly.

Thanks for reading — I hope you found it useful and insightful.

Feel free to share feedback, connect, or explore more projects in the Generative AI Lab.