The Chain Reaction That Built Modern AI

In less than a decade, artificial intelligence has gone from niche academic models to everyday assistants that generate images, answer questions, and write code. Behind this explosion of capabilities lies a series of architectural breakthroughs, scaling laws, training methods, and open-source movements — each unlocking a new wave of progress.

This blog traces the defining moments in that evolution:

From the Transformer architecture in 2017 to the rise of ChatGPT, multimodal models, and custom fine-tuning tools that now run on personal devices.

Rather than cover everything, this post focuses on the innovations that changed the direction of the field — the ideas that made what came next possible.

If you want to understand how we got from “attention is all you need” to today’s AI-powered tools and assistants, you are in the right place.

This post is part of the Generative AI Lab, a public repository that explores creative and practical uses of LLMs, Vision-Language Models (VLMs), and multimodal AI pipelines. If you are curious about how these systems can be chained together to automate creative workflows, feel free to explore the other blogs in the repository to discover more exciting applications.

📚 Table of Contents

- 🤖 Transformers: The Architectural Breakthrough (2017)

- 🧠 BERT: Pretraining for Understanding (2018)

- 📏 GPT-2 & GPT-3: Scaling and Generating (2019–2020)

- 🖼️ Vision Transformers (ViT): Attention Comes to Vision (2020)

- 🔗 CLIP: Bridging Vision and Language (2021)

- 🦕 DINO: Self-Supervised Vision with Emerging Semantics (2021)

- 🎨 DALL·E & Stable Diffusion: Generative Image Models (2021–2022)

- 🦙 LLaMA: Open Foundation Models (2023)

- 🛠️ LoRA + Quantization: Fine-Tuning for Everyone (2023)

- 💬 ChatGPT, RLHF, and Generative Assistants (2022–2023)

- 🧬 No Parthenogenesis: AI Progress Has a Lineage

🤖 Transformers: The Architectural Breakthrough (2017)

In 2017, Vaswani et al. introduced the Transformer, a radically new architecture that reshaped modern AI.

Before Transformers, tasks like machine translation relied heavily on RNNs (Recurrent Neural Networks) and LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks), which processed text sequentially—one word at a time. This made training slow and limited the ability to learn long-range dependencies, such as connections between words that are far apart.

Transformers eliminated recurrence entirely. Instead, they used a mechanism called self-attention, allowing the model to process all words in a sentence at once and determine which ones are most relevant to each position. This innovation enabled parallel processing, faster training, and deeper contextual understanding.

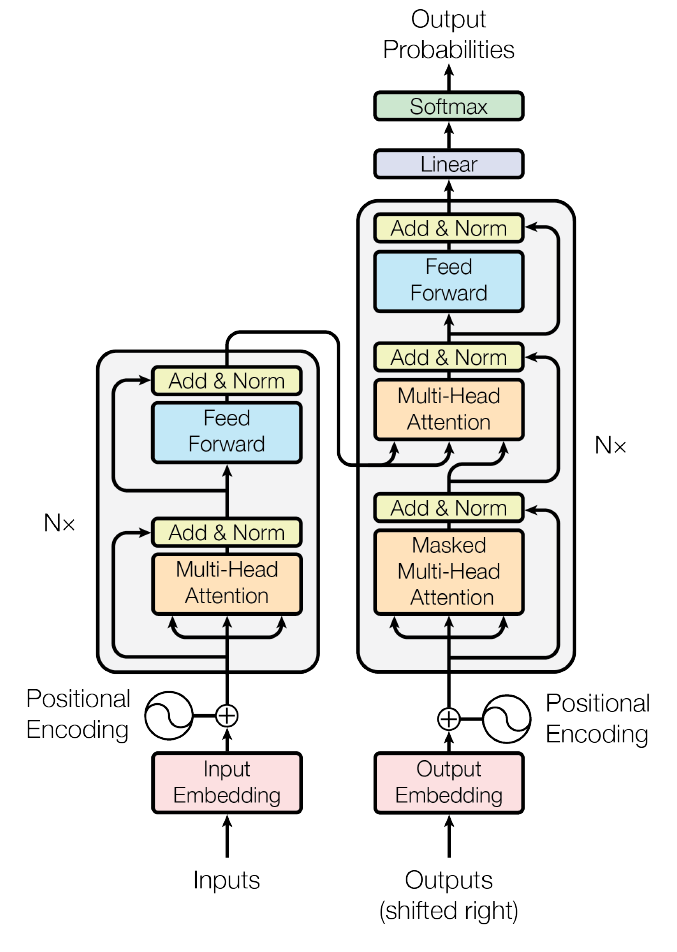

The Transformer - model architecture. Adapted from Vaswani et al. (2017).

What Is Self-Attention?

Self-attention allows each word to dynamically attend to every other word in the sequence, regardless of their position.

Consider the sentence:

“The cat sat on the mat because it was warm.”

To understand what “it” refers to, the model needs to associate “it” with “the mat.” Traditional models often struggled with this unless the words were close together. Self-attention enables the model to assign higher importance to semantically related words, allowing “it” to effectively focus on “the mat” and form a contextualized representation.

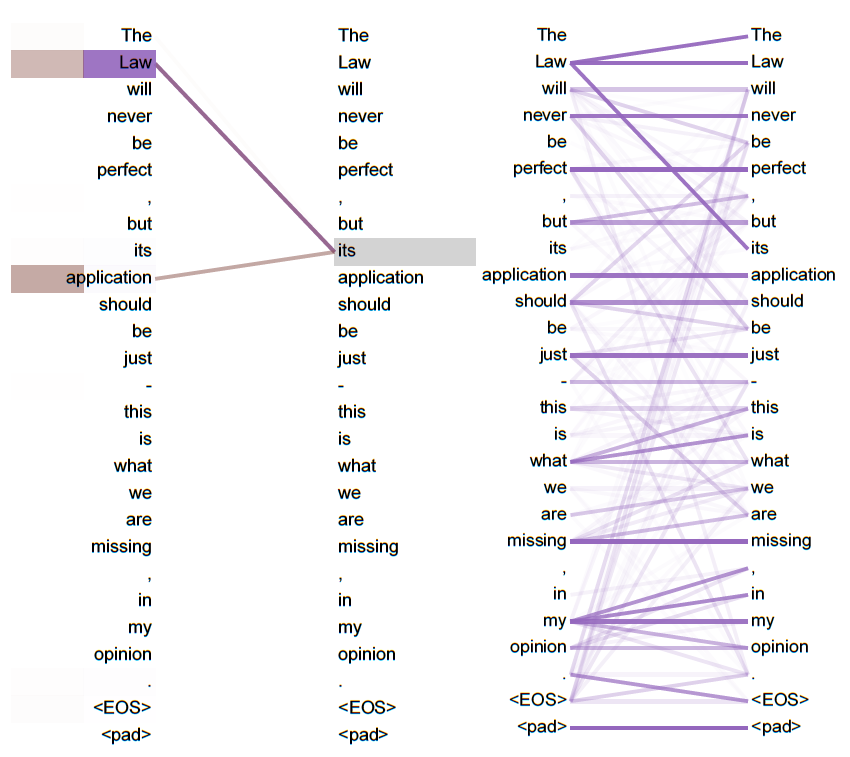

The following example from the original paper demonstrates how different attention heads track relationships across a sentence:

- One head links the possessive “its” to its referent “Law”, performing what is known as anaphora resolution—the process of determining what a pronoun refers to.

- Another head focuses on “application”, showing how attention can follow grammatical or semantic roles.

Visualizing attention from two different heads in the Transformer’s encoder (layer 5). The model captures how the word “its” relates to “Law” and “application”, learning grammatical and semantic dependencies during training. Adapted from Vaswani et al. (2017).

Why It Mattered

Transformers removed the need for recurrence and convolution, relying solely on stacked self-attention and feed-forward layers. This architectural shift enabled:

- Faster training through full parallelization

- Better handling of long-range dependencies

- Scalability to large datasets and model sizes

- Powered BERT for language understanding

- Scaled to GPT-3 for text generation

- Adapted to vision through ViT

- Enabled multimodal models like CLIP, SAM, and LLaVA

This was not just a new model — it was a new paradigm.

🧠 BERT: Pretraining for Understanding (2018)

In 2018, researchers at Google introduced BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, a breakthrough model that fundamentally changed how machines learn to understand language.

While Transformers had already shown impressive results in translation and generation tasks, BERT demonstrated that a Transformer encoder could be pretrained on large volumes of text and then fine-tuned for a variety of downstream tasks — achieving state-of-the-art results across the board.

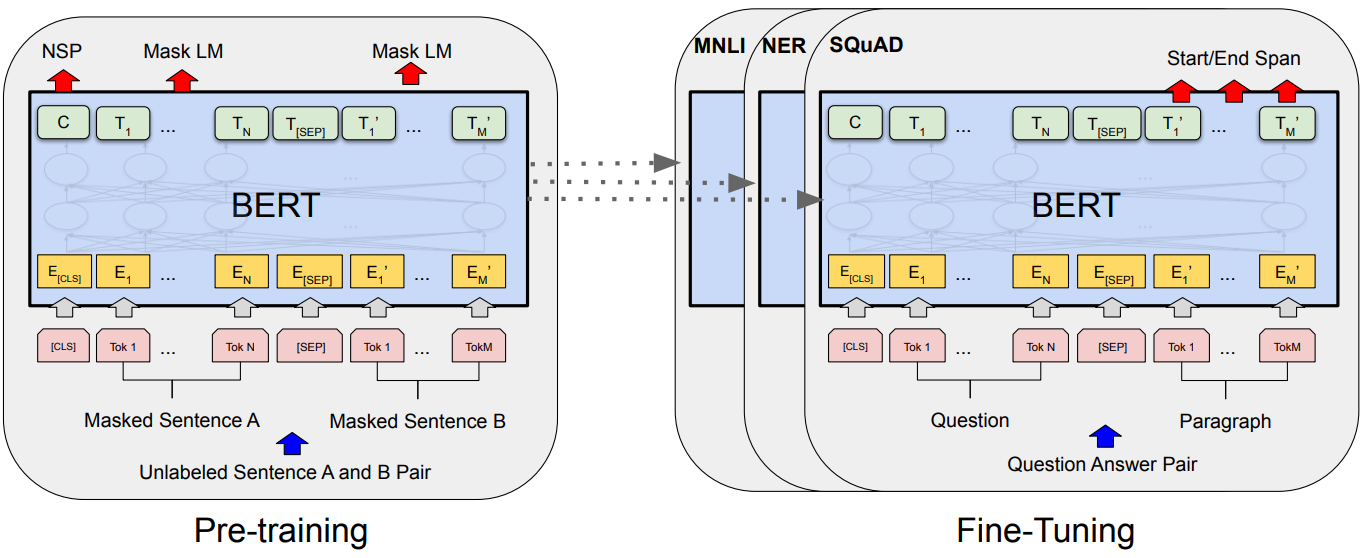

BERT pre-training and fine-tuning flow. Adapted from Devlin et al. (2018).

Pretraining with Masked Language Modeling (MLM)

BERT’s key innovation was introducing Masked Language Modeling (MLM): during pretraining, the model randomly masks words in a sentence and learns to predict them using context from both sides — not just the words before or after.

BERT uses context from both directions to predict the masked word “mat”:

“The cat sat on the [MASK] because it was warm.”

This bidirectional training contrasts with models like GPT, which are trained to predict the next word using only the left-side context:

GPT predicts “mat” using only the left context — it never sees what comes after:

“The cat sat on the”

BERT’s ability to attend to both preceding and following words allowed it to develop deep contextual understanding, ideal for natural language understanding tasks.

BERT also introduced a secondary objective, Next Sentence Prediction (NSP), where the model learns whether two sentences appear in sequence in the original text. While later models like RoBERTa removed NSP without performance loss, it was part of BERT’s original design to improve inter-sentence coherence.

Why It Mattered

BERT significantly raised the bar across dozens of natural language understanding (NLU) tasks:

- ✅ Named entity recognition

- ✅ Question answering

- ✅ Sentiment analysis

- ✅ Natural language inference

It enabled researchers and developers to fine-tune a single pretrained model for a variety of downstream tasks using minimal labeled data — unlocking both high performance and broad accessibility.

BERT’s success paved the way for a new generation of encoder-based models:

- RoBERTa (by Meta): a robustly optimized variant that removed NSP and extended training

- DistilBERT, ALBERT, and TinyBERT: smaller, faster models designed for efficient deployment

- T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer): generalized the framework across tasks using a unified text-to-text format

The core idea of masked language modeling also influenced vision models like DINO and MAE, which learn by predicting missing parts of an image.

Most importantly, BERT helped shift the field from task-specific architectures to foundation models — large, general-purpose neural networks that can be adapted to a wide range of domains with minimal customization.

📏 GPT-2 & GPT-3: Scaling and Generating (2019–2020)

Following the success of encoder-based models like BERT, OpenAI took a different path — focusing not on understanding, but on generating text.

In 2019, OpenAI introduced GPT-2, a large-scale autoregressive language model trained to predict the next word in a sentence, one token at a time. It was followed in 2020 by GPT-3, which scaled the same approach to 175 billion parameters, demonstrating that sheer scale could unlock surprising new capabilities.

GPT stands for Generative Pretrained Transformer — a Transformer decoder trained to generate coherent text from left to right.

Training with Next-Token Prediction

Unlike BERT’s bidirectional masked language modeling, GPT models are trained left-to-right using a simple objective: Given the previous tokens, predict the next one.

“The cat sat on the” → “mat”

GPT never sees future context during training. This constraint makes it ideal for open-ended generation tasks, where each new word is generated based only on what came before.

Despite the simplicity of this setup, scaling up model size and training data led to emergent behaviors — such as few-shot learning, in-context reasoning, and stylistic adaptation — without explicit task-specific tuning.

Scaling Up = Learning More from Context

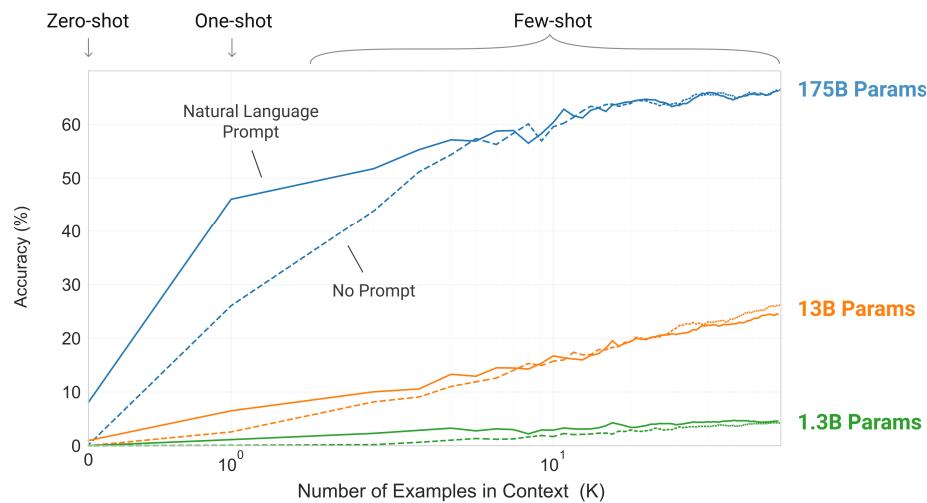

GPT-3 scaled up the GPT-2 architecture by over 100× in size and data, proving that massive scale alone could dramatically improve generalization. Notably, larger models became more sample-efficient: they could solve new tasks just by seeing a few examples in the prompt — no parameter updates needed.

This is illustrated below, where the largest model (175B) achieves high accuracy on a task after just a handful of examples. Smaller models (13B, 1.3B) barely improve, even with more examples — highlighting that scaling unlocks in-context learning.

Larger models learn better from fewer examples. With only prompt-level context, GPT-3 demonstrates few-shot generalization across tasks. Adapted from Brown et al. (2020).

Why It Mattered

GPT-2 and GPT-3 proved that scale itself is an accelerator of capability — a model trained on a generic next-word objective could generate coherent essays, answer questions, write code, and perform translation, all from a single prompt.

This shift toward zero-shot and few-shot inference enabled models to perform tasks with little or no fine-tuning, just by conditioning on well-structured input.

These models became the backbone of generative AI:

- ChatGPT, Codex, and InstructGPT are all built on GPT-style decoding

- Autoregressive generation is now used in multimodal models like DALL·E, BLIP, and LLaVA

- GPT-style scaling inspired the development of foundation models across modalities, from vision to code

Where BERT helped machines understand, GPT enabled them to speak, write, and reason — marking the start of the generative era in AI.

🖼️ Vision Transformers (ViT): Attention Comes to Vision (2020)

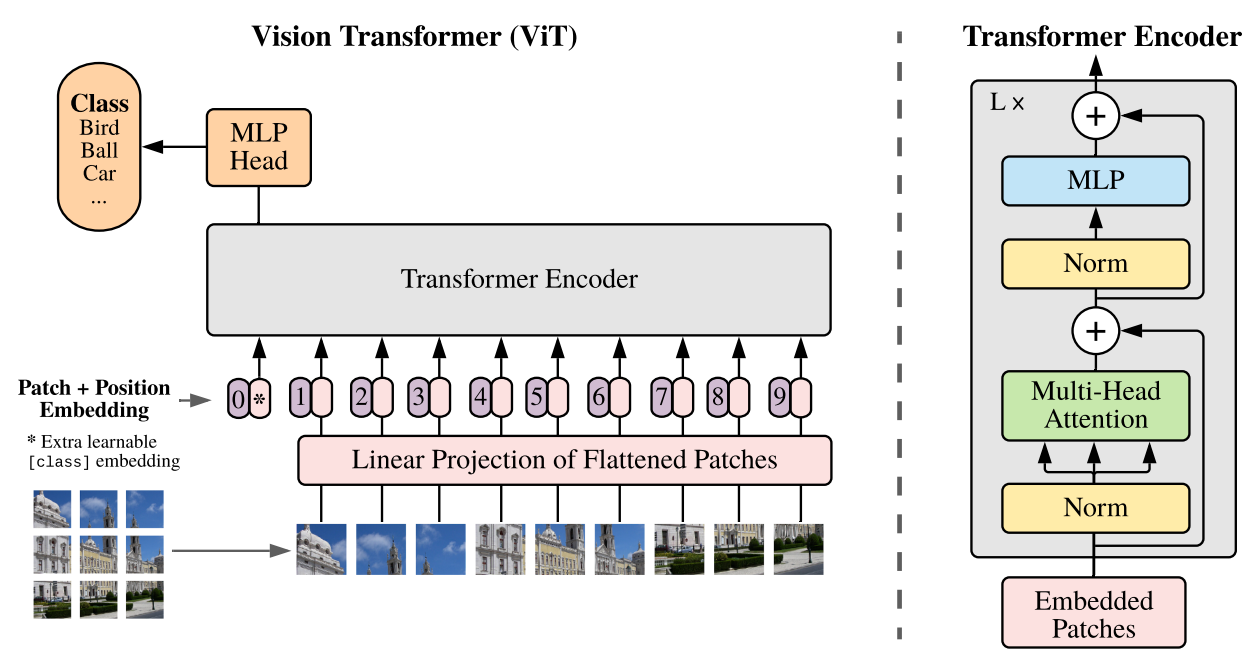

In 2020, researchers at Google Brain introduced ViT: An Image is Worth 16x16 Words, applying the Transformer encoder architecture — originally designed for language — directly to images.

Until then, computer vision had been dominated by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which rely on spatial hierarchies and local receptive fields. ViT replaced convolutions with pure self-attention, showing that the same mechanisms powering language models could also excel at vision.

From Pixels to Patches

ViT divides an image into fixed-size patches (e.g., 16×16 pixels), flattens them into sequences, and feeds them into a standard Transformer encoder — treating each patch like a token in a sentence.

This simple adaptation enabled the model to:

- Learn global relationships across the entire image

- Avoid hand-crafted inductive biases from convolutions

- Scale naturally with data and compute

Like words in a sentence, patches are embedded and passed through self-attention layers — allowing ViT to capture long-range dependencies in visual input.

ViT splits an image into fixed-size patches and feeds them to a Transformer encoder, just like tokens in a sentence. Adapted from Dosovitskiy et al. (2020).

Why It Mattered

ViT showed that attention alone could match — or even surpass — CNNs on large-scale vision tasks, given enough data and training.

This architectural shift had lasting influence:

- ViT became the backbone for self-supervised learning methods like DINO, MAE, and iBOT

- It laid the foundation for multimodal models like CLIP, BLIP, and LLaVA

- Inspired new vision-specific variants like the Swin Transformer, which adds spatial hierarchy

Just as Transformers revolutionized NLP by replacing recurrence, ViT signaled a similar turning point in computer vision — showing that a unified architecture could scale across modalities.

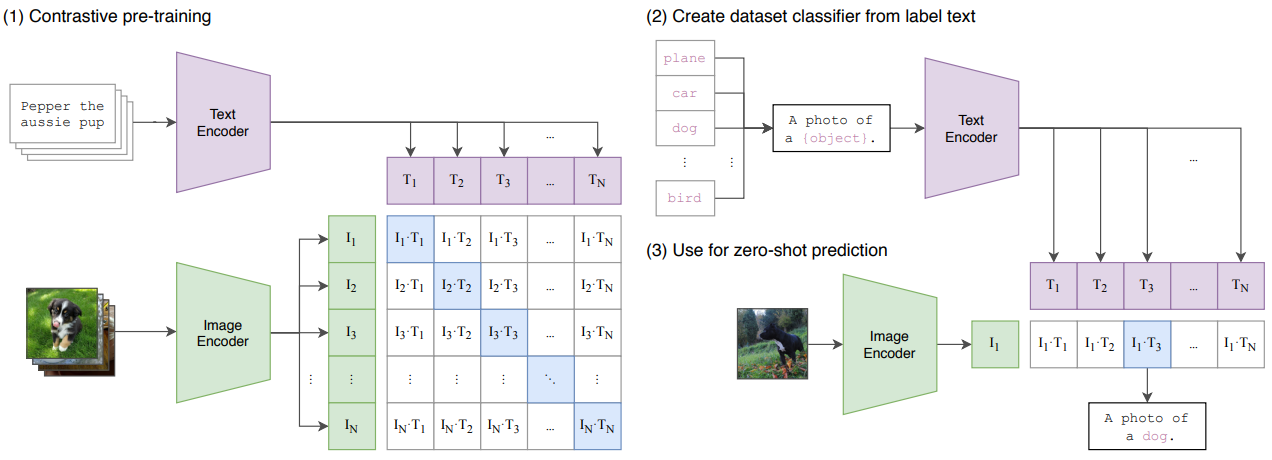

🔗 CLIP: Bridging Vision and Language (2021)

In 2021, OpenAI introduced CLIP: Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision, a model that moved beyond fixed object labels by learning directly from image–text pairs scraped from the internet.

Most vision models at the time were trained to classify a fixed set of predefined categories. This limited their flexibility — adapting them to new concepts required collecting labeled datasets for every task. CLIP flipped the paradigm: instead of predicting labels, it learned to match images to free-form text descriptions, using language as a universal supervision signal.

Joint Training with Contrastive Learning

CLIP consists of two encoders:

- A Vision Transformer (ViT) for images

- A Transformer-based encoder for natural language

It is trained with a simple contrastive objective:

Bring matching image–text pairs closer in embedding space, and push mismatched ones apart.

This allows CLIP to map both images and texts into the same latent space, where semantic similarity aligns — enabling zero-shot classification, retrieval, and more.

CLIP learns by pairing images and texts in a shared embedding space. At inference, it compares an input image to text prompts like “a photo of a dog” to make zero-shot predictions. Adapted from Radford et al. (2021).

Why It Mattered

CLIP marked a turning point in vision AI by showing that models could learn powerful image representations from natural language alone — without any task-specific labels.

- Enabled zero-shot transfer to dozens of vision tasks, from object recognition and OCR to video action classification and geo-localization

- Matched the performance of models like ResNet-50 on ImageNet — without seeing a single training label from that dataset

- Used as a building block in DALL·E 2, BLIP, LLaVA, and more

- Inspired a wave of contrastive and cross-modal learning methods

CLIP made it possible to reference or describe visual concepts with free-form prompts, turning raw language into a control mechanism for vision systems. It was not just a better image model — it redefined how image models are trained.

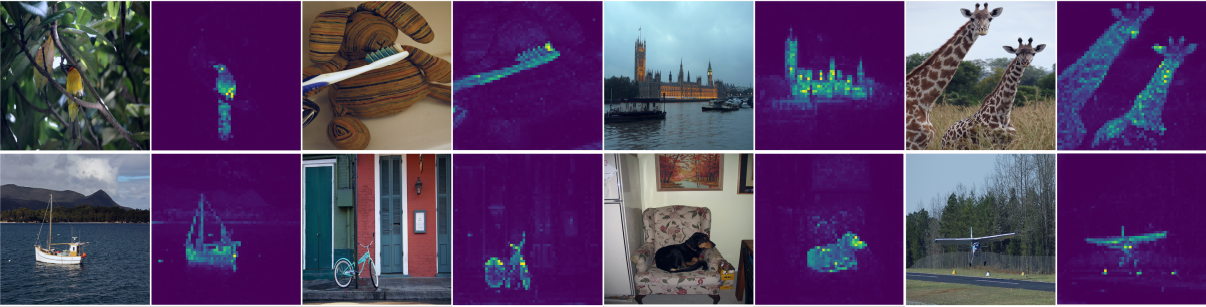

🦕 DINO: Self-Supervised Vision with Emerging Semantics (2021)

In 2021, Meta AI introduced DINO: Self-Distillation with No Labels, a framework that showed Vision Transformers (ViTs) could learn to recognize meaningful visual concepts — without seeing a single label.

Unlike traditional models trained to classify objects, segment images, or detect bounding boxes, DINO was trained with no supervision at all. Its only goal: learn to produce rich and stable image features — useful vector representations that capture what the image is about, not just how it looks.

Learning by Matching Views — Not Labels

DINO uses two networks:

- A student, which learns through gradient descent

- A teacher, which slowly tracks the student (no gradients)

Both are given different views of the same image — crops, color shifts, flips. Each network turns its image into a feature vector (e.g., a 768-dimensional array).

The student is trained to match the teacher’s output. This is called self-distillation without labels.

Even though the views are different, the content is the same. The model learns to focus on what matters — the dog, not the background; the airplane, not the trees.

Think of it this way:

- A person sees a dog from the front, then again from the side — and still knows it is a dog.

- DINO learns the same way — not by being told “this is a dog”, but by learning what stays consistent across views.

It is Not a Classifier — It Learns What to Look At

DINO is not trained to assign categories.

Instead, it builds a feature space where images with similar content land close together — even without knowing what the content is.

- A cluster of boats will be near other boats

- A giraffe will land close to other tall, spotted animals

- You can plug in a simple classifier on top — or just visualize the features

That is where attention maps come in.

Attention heads in DINO-trained ViTs highlight meaningful regions — even without being told what objects are. Adapted from Caron et al. (2021).

In the figure above, DINO’s attention heads have learned to focus on the main object in each image — a dog, boat, or bird — without seeing object labels or annotations. The model learns where to look, just by matching views of the same scene.

Why It Mattered

DINO demonstrated that Vision Transformers could learn strong, general-purpose visual features through self-supervision alone.

- Enabled large-scale training on unlabeled data

- Learned object-centric attention — objects “pop out” in attention heads

- Outperformed many supervised models in feature quality (e.g., 80.1% Top-1 on ImageNet with linear probing)

- Became the foundation for tasks like classification, segmentation, retrieval

- Influenced models like MAE, iBOT, SEER, and more

DINO proved that powerful visual understanding can emerge — not from labels, but from structure in the data itself.

🎨 DALL·E & Stable Diffusion: Generative Image Models (2021–2022)

In 2021–2022, image generation from text prompts leapt forward with DALL·E 2 by OpenAI and Stable Diffusion by CompVis — two models that made visual creativity programmable.

They did not just caption or classify images — they synthesized entirely new ones, guided only by language.

From Prompt to Pixels — and Beyond

DALL·E 2 introduced a two-step architecture:

- A CLIP-based encoder maps the text prompt into a rich vision–language embedding space.

- A diffusion decoder then generates images that match the semantics of this embedding.

This separation allows the model to capture high-level concepts from language and render them as controllable visual compositions. Unlike previous GAN-based models, DALL·E 2 benefits from diffusion’s stability, diversity, and precision, producing multiple coherent results with fine-grained prompt control.

Stable Diffusion pushed the architecture further by introducing a latent diffusion model (LDM) Rombach et al., 2022. Instead of denoising pixel-space images, it learns to denoise in a compressed latent space using a pretrained autoencoder.

This brought two key benefits:

- 🚀 Efficiency — training and inference are much faster and require less GPU memory

- 🧩 Flexibility — any image modality (inpainting, style transfer, interpolation) can be plugged into the same pipeline

Stable Diffusion used classifier-free guidance to amplify alignment with the text prompt, combining conditioned and unconditioned generations at inference time.

Both models reframed generation as a semantic translation problem — from language to latent space to image — setting the stage for multimodal creativity.

Stable Diffusion’s modular design makes it useful for a range of generative tasks beyond basic text-to-image synthesis — including inpainting, image-to-image translation, and super-resolution.

Examples of Latent Diffusion Models applied to text-to-image generation, inpainting, and super-resolution — all using the same underlying latent architecture. From Rombach et al. (2022).

Why It Mattered

DALL·E and Stable Diffusion transformed image generation into an open, language-driven creative process.

- DALL·E 2 introduced CLIP-guided diffusion for high-quality, controllable generations

- Stable Diffusion pioneered latent-space generation, enabling local, real-time synthesis

- Democratized access through open weights and tools — spawning a global creator ecosystem

- Powered downstream tasks: inpainting, outpainting, style transfer, and image editing

They did not just generate images — they kicked off the prompt-driven visual era in AI.

🦙 LLaMA: Open Foundation Models (2023)

In 2023, Meta released LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, a family of transformer models ranging from 7B to 65B parameters. It marked a shift away from the “bigger is better” mindset — showing that smaller, well-trained models could rival massive proprietary ones.

Efficient Scaling for Smaller Models

The core idea behind LLaMA was that model quality comes from training strategy, not just parameter count. Meta focused on:

- A clean, diverse 1.4T-token dataset, emphasizing scientific and technical sources

- Smaller vocabularies and efficient positional encodings

- Longer training for smaller models, extending up to 1T tokens — far beyond what earlier scaling laws recommended

Instead of stopping at a compute-efficient budget, Meta trained smaller models further — trading longer training for cheaper, faster inference later.

This approach paid off: LLaMA-13B outperformed GPT-3 (175B) on multiple benchmarks, despite being nearly 10× smaller.

Training loss vs. tokens for LLaMA models. Smaller models continue improving with more data — a deliberate choice to enhance inference efficiency. Adapted from Touvron et al. (2023).

Why It Mattered

Unlike previous high-performing LLMs, LLaMA models were released with full weights, not just an API — opening the door to wide experimentation and customization.

- Proved that well-trained small models can compete with giants

- Sparked the open-source LLM wave — powering Alpaca, Vicuna, Mistral, and more

- Enabled deployment on local devices and integration in multimodal systems like LLaVA

- Laid the foundation for RAG pipelines and sovereign AI efforts

LLaMA did not just shrink models — it democratized access to them.

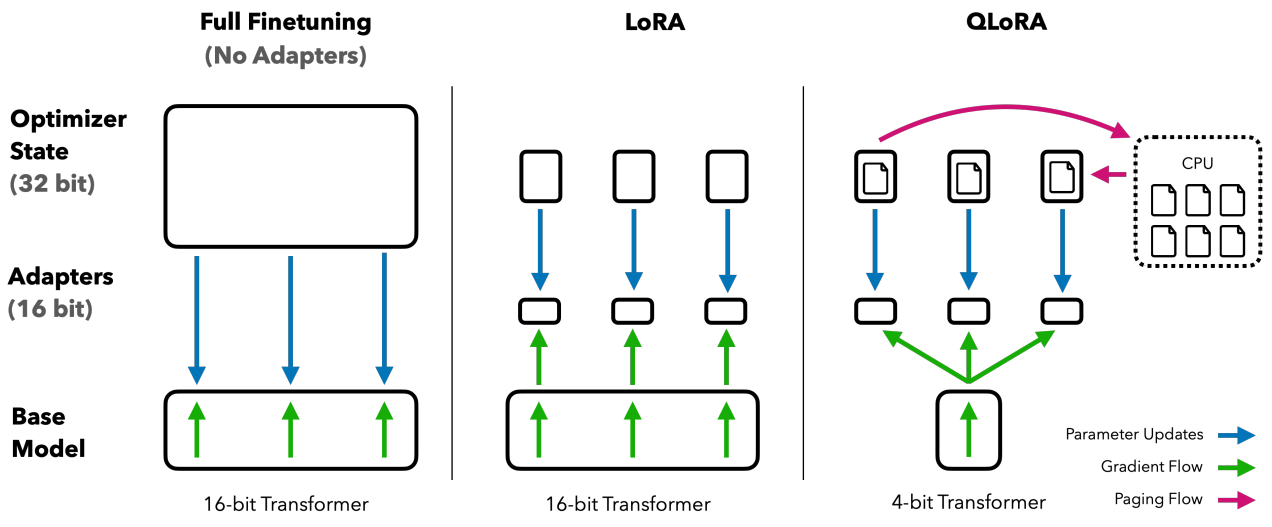

🛠️ LoRA + Quantization: Fine-Tuning for Everyone (2023)

In 2023, two breakthroughs made it possible to fine-tune large language models on modest hardware: LoRA for efficient training, and QLoRA for low-memory inference and tuning. Together, they brought model customization into reach for individuals and small teams — no data center required.

Lightweight Adaptation with Minimal Compute

LoRA Hu et al., 2021 introduced a simple idea: instead of updating all model weights, insert small trainable adapter layers into a frozen base model. It is like attaching flexible patches to a locked system — targeted, efficient, and non-destructive.

QLoRA Dettmers et al., 2023 took it further by:

- Quantizing the model to 4-bit precision

- Using paged optimizers to offload memory to CPU when needed

- Allowing full fine-tuning of 65B+ models on a single 24GB GPU

LoRA minimizes what you train. QLoRA minimizes what you load. Together, they make fine-tuning cheap, fast, and portable.

The difference between full fine-tuning, LoRA, and QLoRA is best seen visually.

How memory usage is reduced across fine-tuning methods. Adapted from Dettmers et al. (2023).

In full fine-tuning, everything is updated — requiring massive memory and compute.

LoRA freezes the base model and trains lightweight adapters instead.

QLoRA compresses the model and offloads optimizer state to CPU — enabling large-scale fine-tuning on consumer hardware.

This allows developers to fine-tune billion-parameter models locally — something previously reserved for industrial-scale labs.

If you have fine-tuned a model with Hugging Face’s peft library, you have already used LoRA. It is now the standard way to adapt large models efficiently — whether for chat, code, or domain-specific applications.

If you have ever loaded a model in 4-bit using bitsandbytes, you have likely benefited from QLoRA — whether you realized it or not.

Why It Mattered

LoRA and QLoRA did not just optimize model size — they opened up the fine-tuning frontier.

- Enabled fine-tuning on laptops and consumer GPUs

- Became standard in open releases (e.g. Mistral LoRA adapters)

- Powered the development of custom, task-specific models

- Integrated into Hugging Face’s transformers and PEFT stacks

They turned massive language models into adaptable, personal tools.

💬 ChatGPT, RLHF, and Generative Assistants (2022–2023)

In late 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT, a conversational interface built on GPT-3.5 and fine-tuned with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). It marked a major turning point: large language models were no longer just research tools — they became intuitive, helpful, and usable by anyone.

Aligning Language Models with Human Intent

ChatGPT was based on lessons from InstructGPT, which showed that users preferred models fine-tuned to follow instructions — even if they were technically less accurate on benchmarks.

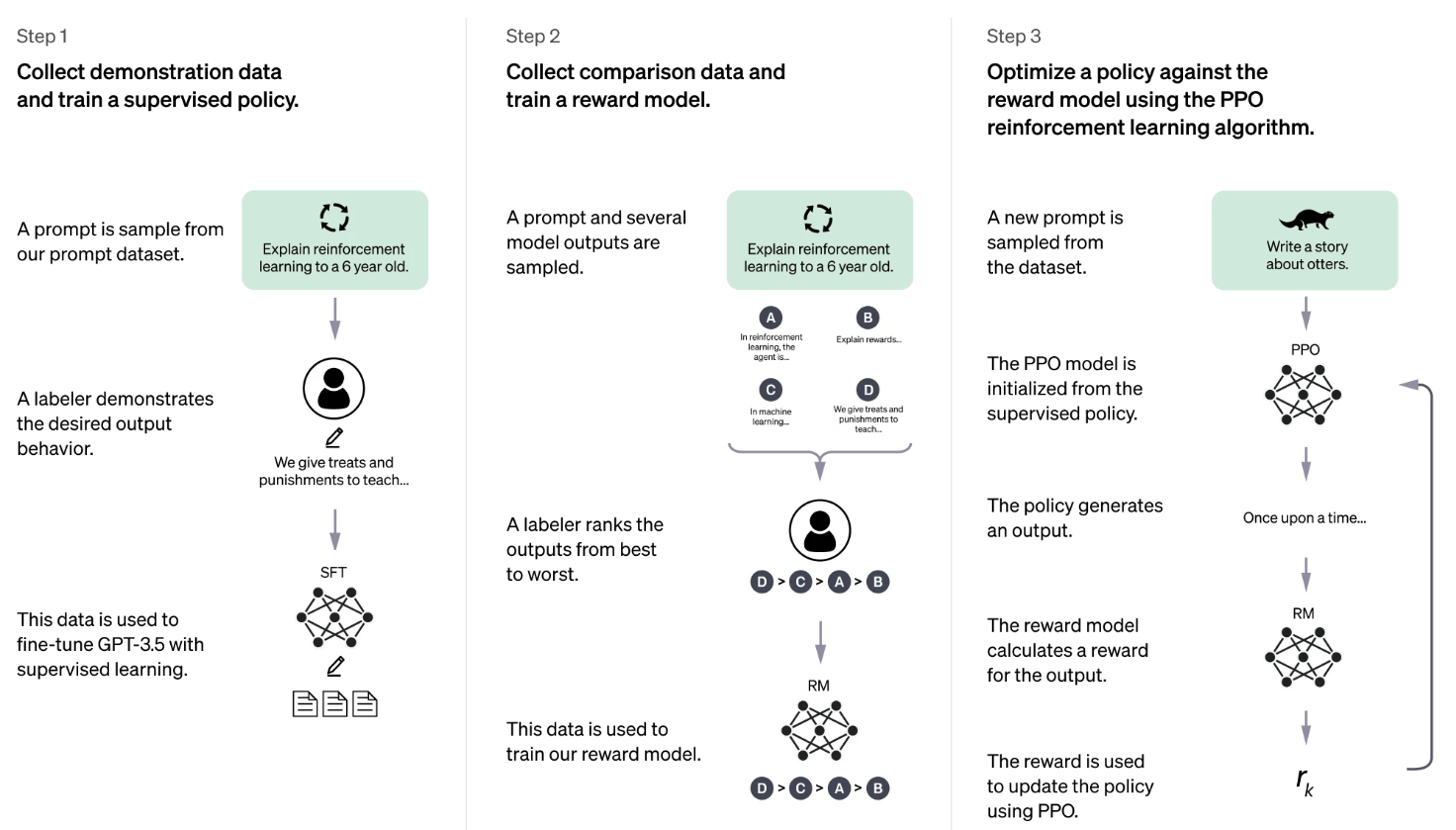

The core innovation was RLHF:

- Start with a pretrained model

- Collect human feedback on model responses

- Train a reward model to reflect preferences

- Fine-tune the LLM using reinforcement learning (PPO or DPO)

This process aligned the model with human values and expectations, encouraging helpful, harmless, and honest behavior — critical for real-world deployment.

Think of RLHF as giving the model a sense of social intelligence — not just grammar, but grace.

How RLHF works in practice: human demonstrations → preference modeling → reward-based fine-tuning. Adapted from OpenAI’s ChatGPT page.

Why It Mattered

ChatGPT was not just a product — it was a shift in how people interact with language models.

- Brought human-aligned outputs to the forefront of model design

- Made LLMs conversational, accessible, and context-aware

- Inspired adoption of RLHF in models like Claude, Gemini, LLaMA-2-Chat, and Mistral-Instruct

- Set the foundation for assistant-style UX: memory, personas, tool use, and more

ChatGPT turned LLMs from language generators into interactive agents — sparking the era of generative AI assistants.

🧬 No Parthenogenesis: AI Progress Has a Lineage

AI’s breakthroughs may feel sudden, but none of them emerged in isolation. The models we use today — from vision-language systems to conversational assistants — are the product of carefully stacked innovations.

Each leap was made possible by the one before:

- Transformers unlocked scale

- BERT introduced pretraining and fine-tuning

- GPT proved generation could generalize

- ViT brought attention to vision

- DINO showed that semantics can emerge without labels

- CLIP bridged modalities

- Diffusion made creativity programmable

- LLaMA made foundation models open and efficient

- LoRA and QLoRA brought customization to everyone

- RLHF made models usable — not just capable

There was no spontaneous generation. No parthenogenesis.

Only a chain reaction — data, ideas, and compute cascading forward — transforming what once felt impossible into something intuitive and everyday.

Of course, none of this would have been possible without a mindset of open research and shared progress — where ideas, models, and tools were not just published, but passed forward.

In the next post, we will follow that chain into the present:

2024–2025, where real-time multimodal assistants, long-context models, and agentic AI systems are already redefining what comes next.

We did not get here by accident. And we are not done.

Thanks for reading — I hope you found it useful and insightful.

Feel free to share feedback, connect, or explore more projects in the Generative AI Lab.